June 3, 2021

DRIVE-Safe Act proponents call for greater trust in trained younger drivers

Legislation proposes two-step apprenticeship and hundreds of hours of training on trucks equipped with latest safety technology

Talks of labor shortages and truck driver safety are common themes at industry conferences, in newsletters, editorials and even watercooler conversations — with good reason.

But it’s almost as if labor and driver safety were inversely related: On one hand, relaxing regulations to make trucking easier to enter is decried as a threat to safety. On the other hand, the industry can’t grow unless drivers have more freedom.

Can’t both issues be addressed at the same time?

The Developing Responsible Individuals for a Vibrant Economy (DRIVE-Safe) Act looks to accomplish just that, by promoting better supplemental driver training while hopefully putting a dent in the driver shortage.

The DRIVE-Safe Act proposes a two-step apprenticeship process for drivers once they receive a commercial driver’s license (CDL). The training would require drivers to complete at least 400 hours of on-duty time and 240 hours of driving time under the supervision of an experienced driver riding shotgun. In addition, drivers would receive training on trucks with the latest safety technology, including active braking collision mitigation systems, forward-facing video capture, and a speed governor of 65 mph at the pedal and under adaptive cruise control.

The DRIVE-Safe Act was introduced in 2018 but was reintroduced with bipartisan support in the U.S. House and Senate last month. It primarily focuses on allowing drivers ages 18 to 21 to participate in interstate commerce, which this demographic currently cannot do.

This has squandered many opportunities for young drivers, according to Brian Runnels, Reliance Partners’ director of safety, who believes carriers could benefit greatly from loosening the leash just a bit.

Runnels argues that opening the door to interstate commerce doesn’t necessarily mean that younger drivers will be granted long-haul jobs. Rather, he makes the case that it’ll actually present more opportunities close to home.

“Carriers as a whole would feel much safer with a younger driver in a closed circuit, a relatively short distance like shuttling or hosteling trailers, or moving freight from one facility to another, not necessarily crossing state lines,” Runnels said. “But if the freight is destined for out of state, [young] drivers can’t take it from a manufacturing facility to a warehouse just 2 miles down the road; they’re not allowed to touch it.”

This means that truckers under the age of 21 operating in and around “state line cities” such as Chattanooga and Memphis, Tennessee; Cincinnati; Charlotte, North Carolina; and St. Louis and Kansas City, Missouri, for instance, aren’t allowed to even deliver local loads just because they originated in or are destined for across state lines.

“More local options would be open to 18- to 21-year-old drivers if they drop the intrastate rules, as weird as that sounds,” Runnels said. “These drivers pick up out-of-state loads dropped off in their area and can deliver them or bring them to a drop yard destined for wherever, which right now they can’t do. This would put these drivers in a more controlled area than just letting them run all over the country.”

So far, more than 120 companies and trade associations have joined a coalition in support of the DRIVE-Safe Act. One supporter is The Next Generation in Trucking Association, a nonprofit education accelerator with the goal of promoting CDL driver and diesel technician programs in high schools and community and technical colleges across the United States. Runnels serves on its board of directors.

Next Gen helps better prepare drivers with preliminary training before they actually work toward obtaining their CDLs. Its founder, Lindsey Trent, hopes the passage of the DRIVE-Safe Act would help further her efforts to introduce high school- and college-age students to the trucking industry. Next Gen’s efforts have already come to fruition in some schools through a senior-level course, entailing 219 hours of classroom instruction and 75 hours behind the wheel of a truck.

“Next Gen isn’t going after every teenager; these young participants are interested in driving at a young age and are serious about their truck driving career,” Trent said. “Not only are we trying to push the passage of the DRIVE-Safe Act, but we ultimately want there to be more trained and skilled young drivers out there.”

“There’s over $1.1 billion of federal funding every year that goes to technical education; the trucking industry is missing this,” Trent said in a previous FreightWaves interview. “We are competing against welding, construction and woodworking, but interestingly enough, a lot of those industries need CDL drivers.”

However, not everyone in trucking is on board with the DRIVE-Safe Act. In fact, a coalition of trucking and safety organizations argues that catering to younger drivers would “needlessly endanger the public.” The coalition stated that commercial drivers 19 to 20 years of age are six times more likely to be involved in a fatal crash than all other truckers. It also argued that the industry has a retention crisis on its hands rather than a driver shortage.

Whether younger or older drivers are safer remains up for debate; it really all depends on how you interpret the statistics, Runnels suggests.

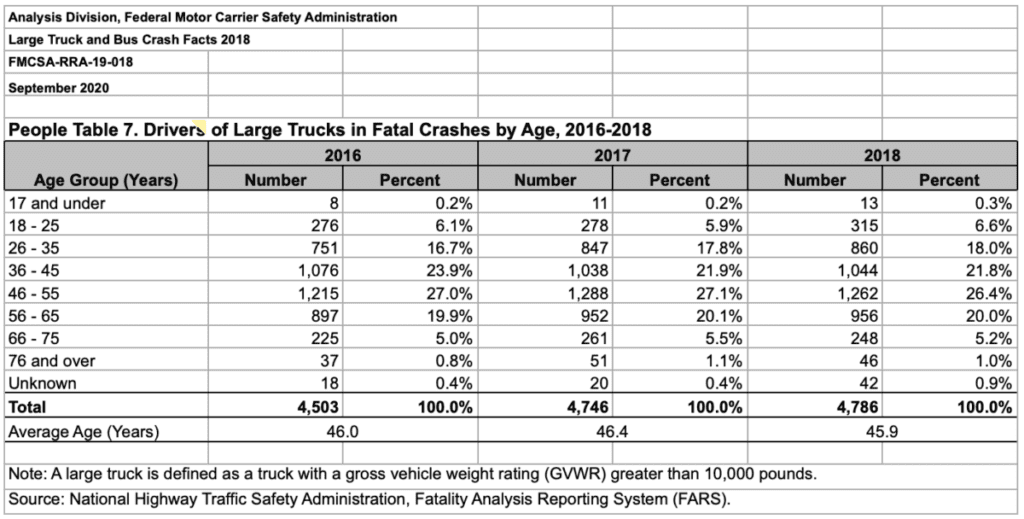

For instance, Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) statistics from 2018 show that the age demographic with the highest percentage of fatal crashes involving large trucks is drivers 46-55 years, at 26.4%. Drivers in the 36-45 age group came in second at 21.8%, followed closely by 56- to 65-year-old drivers at 20%. In fact, only 6.6% of fatal accidents involved drivers 18-25.

One could argue that younger drivers are safer based on these figures alone, but further insight offers a different perspective.

Both Trent and Runnels say most drivers entering the industry today are 38 years old. Further, the median age of commercial drivers is 46, compared to 41 for all other workers. As the majority of commercial drivers predominantly skew older, the fact that they see more accidents seems only logical.

Regardless, the advancing age of truckers is one of the top concerns the industry can’t ignore. Next Gen states that trucking companies will have to hire 890,000 new drivers this decade to keep up with growing freight demand, so all signs point to attracting younger drivers as a viable option.

“I honestly think that it’s going to be an uphill battle. But it’s a matter of starting high school programs and career awareness programs in each state,” Trent said. “There’s a [driver] shortage, and it’s going to continue to increase the prices of consumer goods because there’s not enough people to transport those goods. We’ve got to do something, and in order to keep our economy moving, we have to have more truck drivers.”